Particle Lord: The Importance of being Ernest

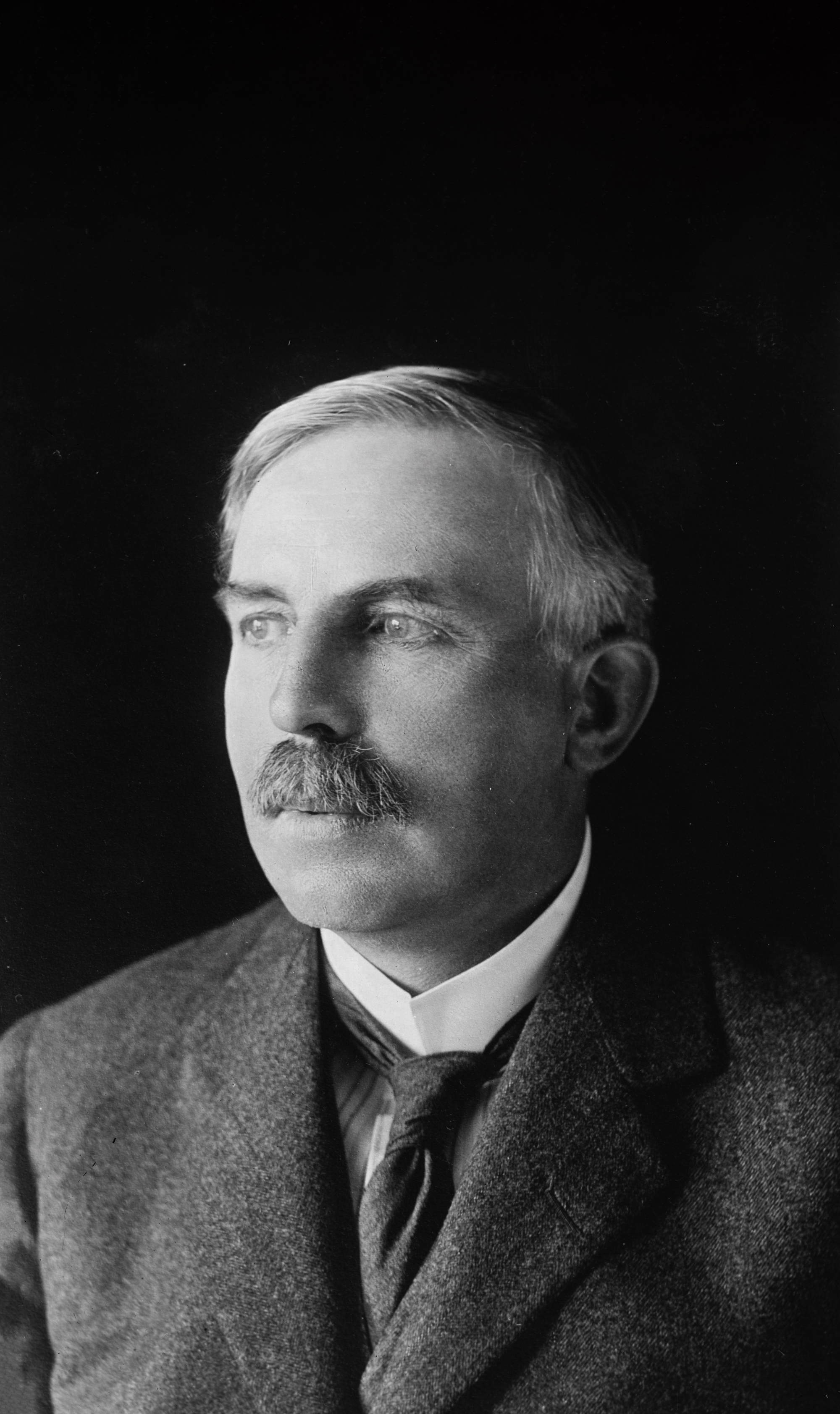

A portrait of Sir Ernest Rutherford taken by a photographer from Herbert photograph studios. Credit Alexander Turnbull Library.

Words: Alistair Hughes

At primary school, two great Kiwi heroes were always impressed upon our young minds with patriotic fervour. Astonishingly, neither were All Blacks, but both had rural beginnings and were given unassuming names beginning with ‘E’, as they began their long journeys toward embedding New Zealand in the awareness of the rest of the world.

The spectacular accomplishment of Sir Edmund Hillary was easy for us to grasp; ‘conquering’ the world’s highest mountain immediately conjured exciting and heroic images. But the achievements of Ernest Lord Rutherford seemed far more esoteric. Being confidently told that he was the first man to ‘split the atom’ certainly sounded important. A statue in Shanghai depicting a very muscular and golden man, (wearing only a moustache), resolutely forcing a giant atomic sphere apart might be close to what we tried to imagine. Or even the equally literal banner from 1923 showing a burly arm wielding a tomahawk about to cleave an innocent glowing orb cowering on an anvil.

Today Ernest Rutherford is known more simply and accurately as the ‘Father of Nuclear Physics’. He was the first to understand and prove that atoms, (named after the greek word for ‘uncuttable’), were themselves made of even smaller particles within a nucleus.

On later putting his revelation to the test, (the famous ‘splitting’), where he transmuted nitrogen into oxygen by bombarding and fissuring its nucleus with alpha particles, Rutherford was quoted as exclaiming: “(I have) broken the machine and touched the ghost of matter.”

Ern, as he was familiarly known, was born the fourth of twelve children near Brightwater, in 1871. Unlike most children, when Rutherford received his first school science book it didn’t remain in his desk, but the actively-minded boy quickly put the experiments within its pages into practice. He was soon found dismantling and reassembling the family clock, or outside during a thunderstorm calculating the distance from the storm centre by counting between thunderclaps. A statue of him as a very young schoolboy, with this book tucked under one arm, stands at Brightwater today.

On turning eleven, his family moved to Havelock and he received further education in a small schoolhouse with over ninety other children. The converted building still exists now, with hopefully less occupants crammed inside, at the Rutherford Backpackers hostel.

Rutherford excelled at school, but his family were financially unable to help the promising young researcher continue his education. However, winning a student scholarship, (on second attempt), allowed him to board at Nelson College for the next three years.

In wonderfully typical Kiwi fashion, he not only became Dux, but also played for the First XV Rugby team.

Another scholarship allowed Rutherford to further his studies at university in Christchurch in 1890. This was an especially busy time in the young man’s life. His mathematical ability granted him an honours year, which enabled Rutherford to develop his reputation as an outstanding researcher in the new field of electromagnetism.

But his continuing education apparently extended beyond the laboratory. During this period he boarded with the young woman who he would later marry, Mary Newton. Mary’s mother was secretary of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which played a crucial role in New Zealand becoming the first country in the world to grant women the vote in 1893.

Rutherford had come from a family of six sisters and a schoolteacher mother. In the year that he had won his University scholarship four of the other nine nation recipients were women, and he studied with them in an academic environment which had always fostered gender equality.

In years to come he was to mentor several women research assistants. Eventually campaigning for England’s stuffily entrenched Cambridge University to afford the same equal rights to women which he had experienced back home, this ‘great booming bear of a man’ and former First XV player also proved himself to be a pioneering feminist.

At 23, Rutherford left New Zealand in 1895 with three university degrees and a science scholarship which enabled him to work as a research assistant at Trinity College, Cambridge. Using the magnetic detector he had invented as a student to set the world distance record for radio wave transmission, Rutherford’s abilities were quickly recognised. Turning to the study of radiation, Rutherford established that there were different forms which he named after letters of the Greek alphabet. So even Marvel comics owes our most famous scientist a debt for their legendary green, gamma-irradiated character, the Hulk.

Offered a professorship in Montreal, Canada, it was here that his further work into the nature of radiation and the atomic transformation of heavy elements led to world recognition and the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. But more importantly, before taking up his post in Canada, Rutherford first came home to New Zealand and married his student sweetheart, Mary.

Eventually returning to Britain in 1907, the now-acclaimed world changer was on something of a roll, inventing a device for the measurement of radioactivity with his assistant Hans Geiger, (which would lead to the famous Geiger counter), and developing his groundbreaking model of the atom. Becoming director of the Cavendish Laboratories where his own career had begun, he was widely acknowledged as an inspiring and generous leader.

With further discoveries, honours began firing at him like his own experimental charged particles. Knighted in 1914, he was then awarded the Order of Merit a decade later. When made Baron Rutherford of Nelson in 1931, Lord Rutherford ensured his coat of arms included a kiwi and a Māori warrior in its design. But it is important to note that, like fellow Kiwi Edmund Hillary, he remained the humble and honest man he had always been. Conscientiously ensuring that his assistants always received due credit, he mentored and guided many future famous scientists towards their own successes. Remaining active until the end, the former New Zealand farm boy, who the New York Times called “the leading explorer of the vast, infinitely complex universe within the atom,” passed away suddenly after gardening at his weekend cottage in 1937.

It was his ‘everyman’ relatability amidst the sometimes abstract achievements which award winning children’s author Maria Gill wanted to highlight in her new book Ernest Rutherford: Just an Ordinary Boy.

“I could see there was a great underlying message within Ernest’s life story about not giving up on your dreams. I wanted readers to realise he was just an ordinary kid like them, who worked hard to get where he ended up and persevered even when he encountered ‘roadblocks’.”

Maria’s book, a richly illustrated retelling for younger readers, launched at the beginning of the month at the Christchurch Arts Centre. She recounts that this is also where the project began: “I was lucky enough to get an Arts Centre residency and to immerse myself in the Rutherford Den Museum, soaking up the atmosphere where Ernest Rutherford went to university. His story came easily, it just flowed from my fingers.”